Antonio D’Amore, Figlio di Montefalcione

My Great-Grandfather Antonio D'Amore was born on March 23, 1869, in Montefalcione, Avellino, Italy.

Antonio’s father, Ferdinando D’Amore, was 29 when he was born. Ferdinando was the son of Cirillo D’Amore. Cirillo had 8 children, among them were Michelangelo D'Amore, born Apr 15th, 1836, who’s descendants eventually migrated to Boston and Philadelphia, and Daniele D'Amore, born Feb 13th, 1845, who’s descendants migrated to Philadelphia as well.

Antonio’s mother, Maria Grazia Petrillo, was 23. 30 She was born on Jun 1845 in Prata di Principato Ultra, the town next over across the valley to the north from Montefalcione.

Antonio’s first sister Maria Sofia was born on June 16, 1872, in Montefalcione, Avellino, Italy, when Antonio was 3 years old. Maria Sofia would marry Carmine D'Aquino from Prata di Principato Ultra. They would go on to have two daughters, Rose and Mary.

Antonio’s second sister Alessandrina was born on May 26, 1879, in Montefalcione, Avellino, Italy, when Antonio was 10 years old. Alessandrina would marry Raffaele Renna from Prata Di Principato Ultra. They would settle in Long Island and have one son, Sylvester.

Antonio’s brother Federigo Ferdinando was born on October 3, 1881, in Montefalcione, Avellino, Italy, when Antonio was 12 years old. Federigo married Elisabetta Macrini on March 12, 1904, in Manhattan, New York. They had one child during their marriage, Lucia.

Frederigo died on March 30, 1939 at the age of 57: Deputy Sheriff D'Amore and Deputy Sheriff John Miller were killed when their prisoner transport van was involved in an accident. Deputy D'Amore and Miller were transporting six convicts in a heavy prison van to Sing Sing Prison when their van overturned after a collision with an automobile at the corner of East Tremont Avenue and White Plains Road in the Bronx, New York.

When he was 26 years old Antonio married Carmela Isabella, who was born on Jan 27, 1869 in Prata di Principato Ultra, on February 13, 1896, in Prata di Principato Ultra.

At some point in 1898 she would eventually immigrate to America with Antonio when he returned to Prata Di Principato to bring her to America. The legend goes that when immigrating to America with his brother, his wife Carmela was forced to live in the town orphanage in Prata because there was nowhere else for her to stay while Antonio was gone, and then once Antonio was financially able to he returned to Italy, sold whatever property they owned there, and brought Carmela back with him to America.

Antonio and Carmela would have five children in 11 years. Antonio and Carmela’s first child, Maria Grazia was born on December 8, 1896, in Prata di Principato and sadly would pass away on January 11, 1897, when she was less than a year old. Later that year Antonio would decide to immigrate to the United States.

For several decades prior the political and economic climate of southern Italy had been in shambles. In 1861 the Kingdom of Two Sicilies was invaded in an undeclared war by the Piedmonts and the Kingdom of Sardinia, guided by the Savoy (who were in turn manipulated by the Freemasons in a conspiratorial power grab to eliminate the Rothschild banking houses of Naples, secure the entire domain of Italy, and seize it’s wealth for themselves). Tens of thousands of people, men, women, and children were killed, raped, and imprisoned by the Piedmontese soldiers and their Hungarian mercenaries.

Antonio's own father Ferdinando was one of many citizens of Montefalcione who were arrested and imprisioned for defending their home from a marauding army of invaders. The citizens of the former Kingdom of Two Siciles would from then on and still to this day be known as “Southerners” or “Terroni” (dirt people). They were called "brigands" because they dared to resist the unlawful invasion of an outside army which was pillaging and murdering.

The consequences of the annexation of the Kingdom of Sicilies, which had been the third wealthiest nation in Eurpoe at that time behind England and France, to the state of Italy were tragic for Southern Italy as a nation:

The gold reserves of the kingdom of Two Sicilies, which numbered 412 million gold lire, double those of all the other pre-unitary states put together and 16 times those of Piedmont, were stolen by the Piedmontese soldiers and funneled to Piedmont banks.

The majority of factories were dismantled and moved to the North. Laws were re-written to favor factory and industry from the north, and all business relationship ties (domestic and foreign) to businesses from the south were severed.

All church property was confiscated and as a result all schools were closed, some not reopening for many decades later.

In the following years after the unification a brutal repression campaign was conducted by the by the Piedmontese against southern Italians who dared to rebel. More people died as a result than in all the wars of independence put together. The first concentration camps in history were used during this campaign.

The Unification of Italy further broke down the remnants of the feudal land system, which had survived in the south since the Middle Ages, especially where land had been the inalienable property.

The redistribution of land deprived all of the small farmers in the south of land of their own or land they could work and make profit from. All privately held lands were unlawfully seized by the Piedmontese, only to be given back to the “latifondisti”, camorra collaborators, who were awarded arbitrary divisions of land for their prearranged cooperation with the Piedmontese. The once previous self-made landowners were essentially reduced to sharecroppers, having to pay latifondisti to live and work on their own lands. Many remained landless, and plots grew smaller and smaller and so less and less productive, as land was subdivided amongst heirs.

The Diasporra, the mass exodus of Italy, was the direct result of the conditions of the late 1800's brought about by the end of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies and was solely responsible for all of our ancestors leaving Italy.

The loss of jobs and extreme poverty forced millions of “Southern Italians” to emigrate, mostly to North and South America. Nothing was done by the new Italian government to assist and keep in contact with these emigrants or provide support or assistance to their families back home. As a result today there is a large Italian Diaspora worldwide (More people of Italian extraction live abroad than in Italy) but the great majority have lost all ties with their motherland.

Prior to 1900 the majority of Italian immigrants were from northern and central Italy. Annual emigration averaged almost 220,000 in the period 1876 to 1900, and almost 650,000 from 1901 through 1915. The numbers may have even been higher; 14 million from 1876 to 1914, according to another study. This new generation of Italian immigrants was distinctly different in makeup from those that had come before. No longer did the immigrant population consist mostly of Northern Italian artisans and shopkeepers seeking a new market in which to ply their trades. Instead, the vast majority were farmers and laborers looking for a steady source of work—any work. Two-thirds of the migrants who left Italy between 1870 and 1914 were men with traditional skills. Peasants were half of all migrants before 1896.

As the number of Italian emigrants abroad increased, so did their remittances, which encouraged further emigration, In 1896, a government commission on Italian immigration estimated that Italian immigrants sent or took home between $4 million and $30 million each year, and that "the marked increase in the wealth of certain sections of Italy can be traced directly to the money earned in the United States. As transatlantic transportation became more affordable, and as word of American prosperity came via returning immigrants and U.S. recruiters, Italians found it increasingly difficult to resist the call of "L'America".

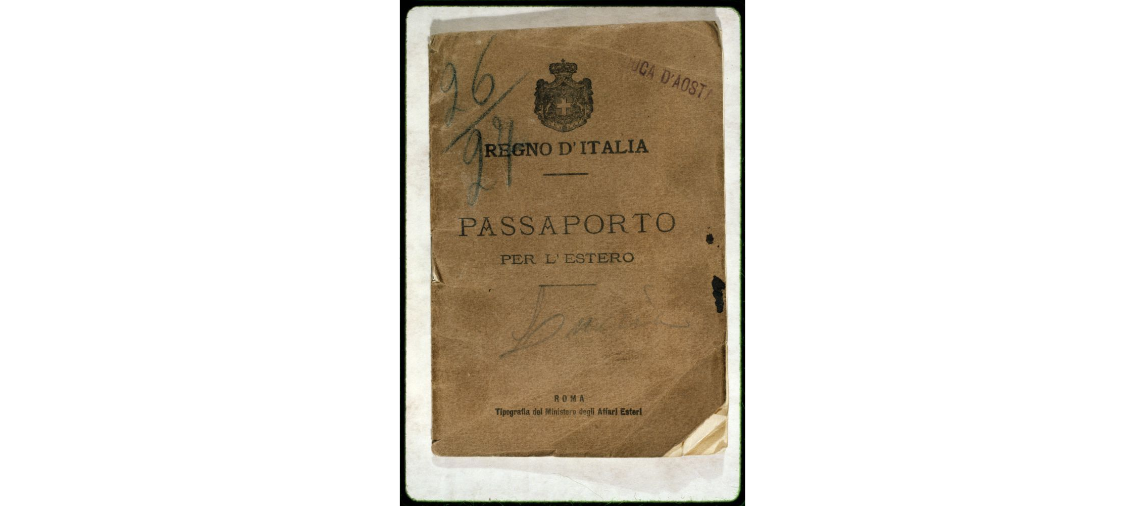

Passport used by Italian immigrants in 1909.

There were a significant number of single men among these immigrants, and many came only to stay a short time. Within five years, between 30 and 50 percent of this generation of immigrants would return home to Italy, where they were known as ritornati.

Dreaming of a better life in America, leaving most of his possessions behind, and bringing only a small trunkful of clothes, on 27 May 1897 at the age of 28, with his brother Federigo D’Amore who was only 15 at the time, Antonio would travel on the ship the Burgundia from Naples to New York City.

The Burgundia

Picture from: Michael J. Anuta, Ships of Our Ancestors (Menominee, MI: Ships of Our Ancestors, 1983; reprint Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co., [1993]), p. 38, courtesy of the Peabody Essex Museum.

SS Burgundia, built in 1882 for the Fabre Line by S. & H. Morton & Co., Leith, Scotland. 2,817 tons; 328 feet long x 40 feet broad; straight bow, 1 funnel, 2 masts; iron construction, screw propulsion, service speed 11 knots. 15 February 1883, maiden voyage, Marseilles-Catania-Palermo-Naples-Gibraltar-New York. December 1905, sold; scrapped at Marseilles [Noel Reginald Pixell Bonsor,North Atlantic Seaway; An Illustrated History of the Passenger Services Linking the Old World with the New (Prescott, Lancashire: T. Stephenson & Sons., 1955), pp. 385 and 666].

Tickets cost somewhere around 210 lira each. Two hundred lira was for the fare and 10 lira was for insurance in case you had to go back.'' At that time, 210 lira was equivalent to about $42. Most passengers rode in steerage, the lowest grade of accommodation on steamships. Passengers would be crammed into mixed berths below decks that were little better than cargo holds. There were few individual bunks, and nowhere to sit to even eat meals. Not that there were necessarily meals; passengers had to bring their own food for the duration of the voyage, which could last as long as 3 weeks.

For a fascinating look into what the ship journey was like probably like for Antonio and his cousins there’s a wonderful article which describes the experience here: Ellis Island National Monument: The Immigrant Journey http://www.ohranger.com/ellis-island/immigration-journey

New York had relatively few Italian residents during its first two centuries. In 1860 only about 1400 New Yorkers were of Italian descent. Most of them eked out a living as dockworkers, fruit vendors, organ grinders, or rag pickers while living in the decaying Five Points slum. However in the 1860s a wave of immigration from Italy began that became a flood by the end of the century. Between 1900 and 1914, almost two million Italians emigrated to America, most arriving in New York. By 1930 NYC was home to over a million Italian Americans – a whopping 17 percent of the city’s population.

Most Italian immigrants came from southern Italy and were contadini (landless farmers) fleeing severe poverty. Some of the earliest arrivals were men seeking work and intending to return home to their families with their earnings (which they often did). Men were sometimes recruited by padroni (labor brokers), who paid their passage, food, and lodging and hired them out as work gangs (pocketing most of the wages). Having little education, many Italian men found work as laborers, digging ditches, paving roads, and building projects like the Brooklyn Bridge, the subway, and Grand Central Terminal. Some created small businesses as street vendors, grocers, and barbers. Italian women and girls often worked in the garment industry.

The Library of Congress has a wonderful presentation entitled “Immigration and Relocation in U.S. History” which describes in detail the Italian American immigration experience of the late 19th century and what it was like to live in the tenements of New York City: https://www.loc.gov/classroom-materials/immigration/italian/a-city-of-villages/

Around the same time period (give or take a couple of years) that Antonio migrated to the United States, the majority of Antonio’s 1st cousins, the children of his dad’s brother Daniele D’Amore, such as Sabatino D’Amore and Olimpia D’Amore, had immigrated to America as well, to the Philadelphia area. Later on the children of his dad’s brother Michelangelo D’Amore, such as Massamino D’Amore, had migrated to the Boston area.

Most of this generation of Italian immigrants took their first steps on U.S. soil in a place that has now become a legend—Ellis Island, or as it was known to Italians, “L'Isola dell Lagrime” (the island of tears). In the 1880s, they numbered 300,000; in the 1890s, 600,000; in the decade after that, more than two million. By 1920, when immigration began to taper off, more than 4 million Italians had come to the United States, and represented more than 10 percent of the nation's foreign-born population.

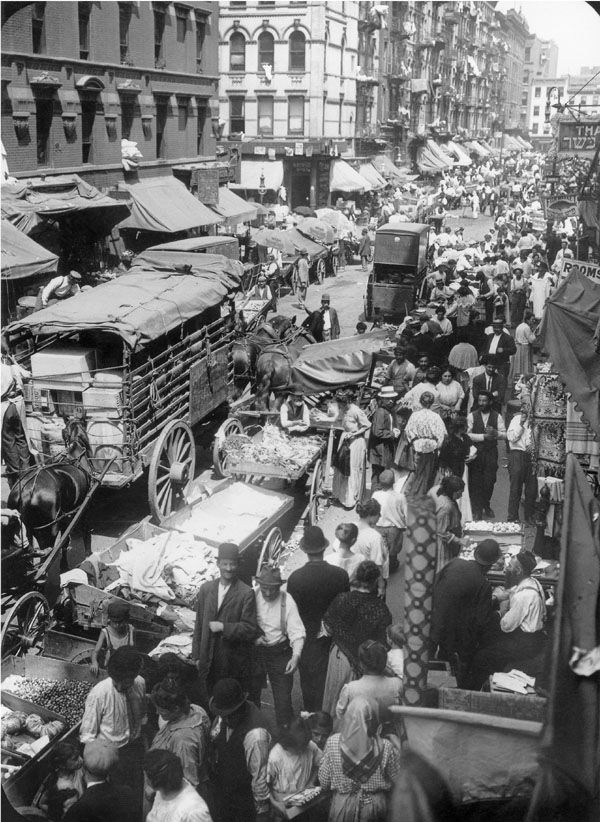

According to census records in the year 1900 Antonio was 31 years old, and his first known address in America was listed as 126 Hester Street on the Lower East Side of Manhattan.

Hester Street, New York City, 1903.

The boom in New York’s population in the late 1800s led to the rise of tenement housing on the Lower East Side. Tenements were low-rise buildings with multiple apartments, which were narrow and typically made up of three rooms. Because rents were cheap, tenement housing was the common choice for new immigrants in New York City. It was common for a family of 10 to live in a 325-square-foot apartment.

By the year 1900, the Lower East Side was packed with more than 700 people per acre, making it the most crowded neighborhood on the planet. This congestion brought with it many hazards, along with many annoyances. Nearly half of the city’s deaths by fire took place in the Lower East Side. Disease was rampant, clean water was hard to come by, and privacy was unheard of. For many immigrant children, their education in American life was acquired in the city streets, where lovers strolled amid streams of raw sewage, vendors offered almost anything for sale, con artists and petty thieves worked the crowds, and horse carriages burdened with goods clogged the muddy roadways.

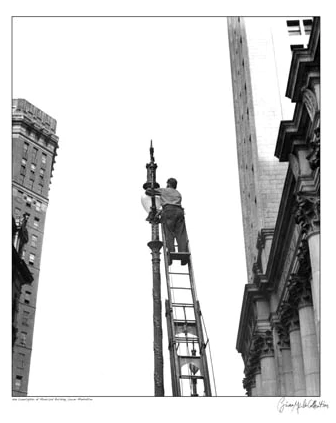

In 1900 Antonio’s profession was listed as a lamplighter. From an always urgent need for street lighting through the years emerged a very important public servant position- the lamplighter. Financed with the town's tax money, a lamplighter made a good, steady living. Many New York City lamplighters were disabled Civil War veterans and understand what havoc Edison's incandescent lights played on their welfare.

Lamplighter Manhattan 1900’s.

The lamplighter's family never went hungry, even in times of turbulence and economic uncertainties. He would start his job before dusk, lighting streetlight after streetlight, going up and down his tall wooden ladder as he serviced each lamp. At day break, he would again go through his ritual of going from lamp to lamp, extinguishing each light, as a new day was about to begin.

Antonio’s daughter Grazia “Grace” D’Amore was born on April 11, 1901, in New York.

Grace went on to become an executive at an oil company in New Jersey. Seen here on a steam ship in Italy, Grace would journey back to Prata Di Principato and donate money to the chiesa di San Giuseppe which was used to rebuild the altar and Madonna statue.

Antonio’s daughter Mary was born on October 4, 1902, in New York (no photo). Mary D’Amore was a legendary cook, responsible for preparing all sorts of wondrous meals.

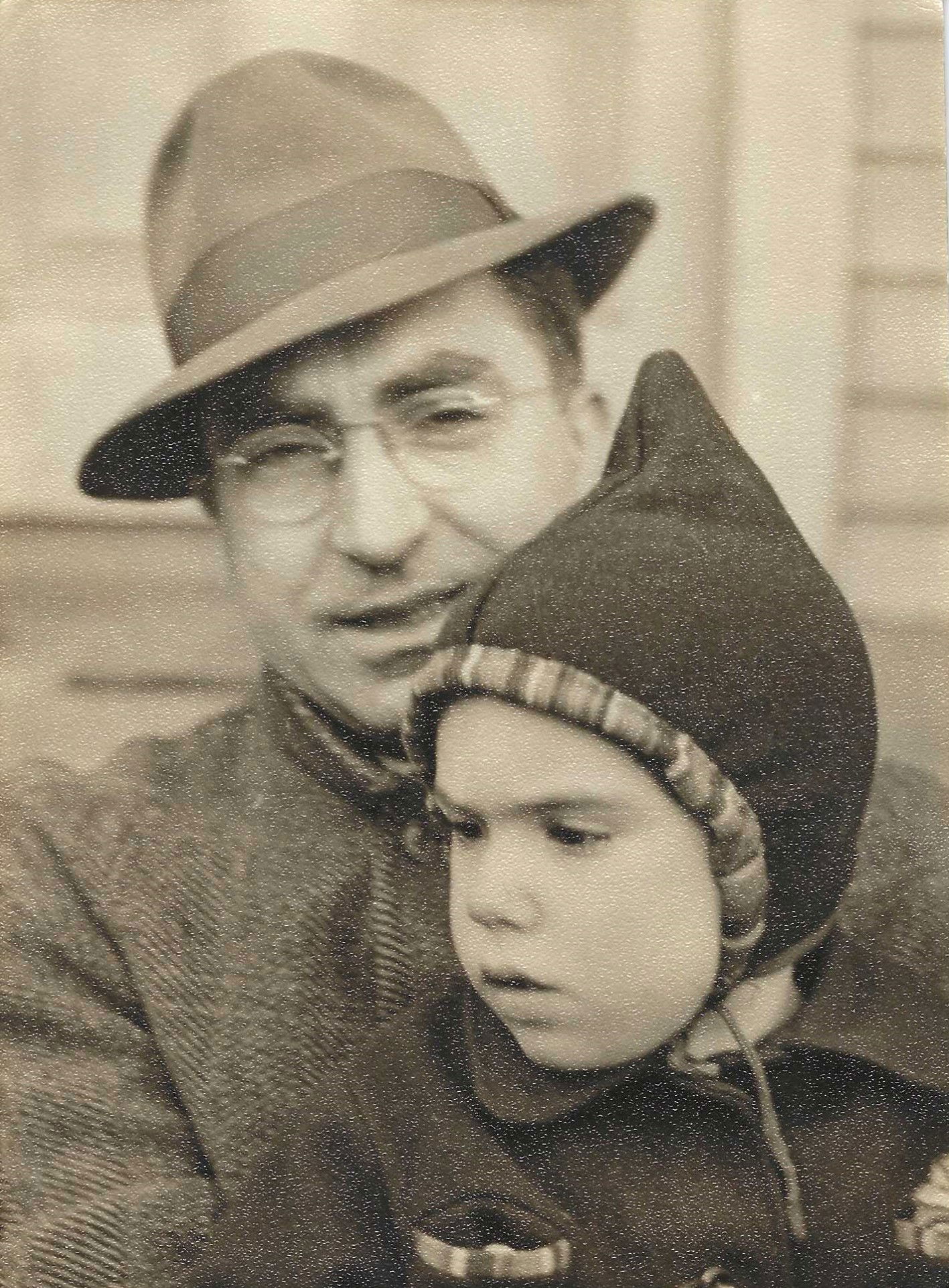

Antonio’s son Francesco Ferdinando was born in 1906 in New York. He would marry Claire Buffalo and they would have one son Edward, seen pictured here as a toddler.

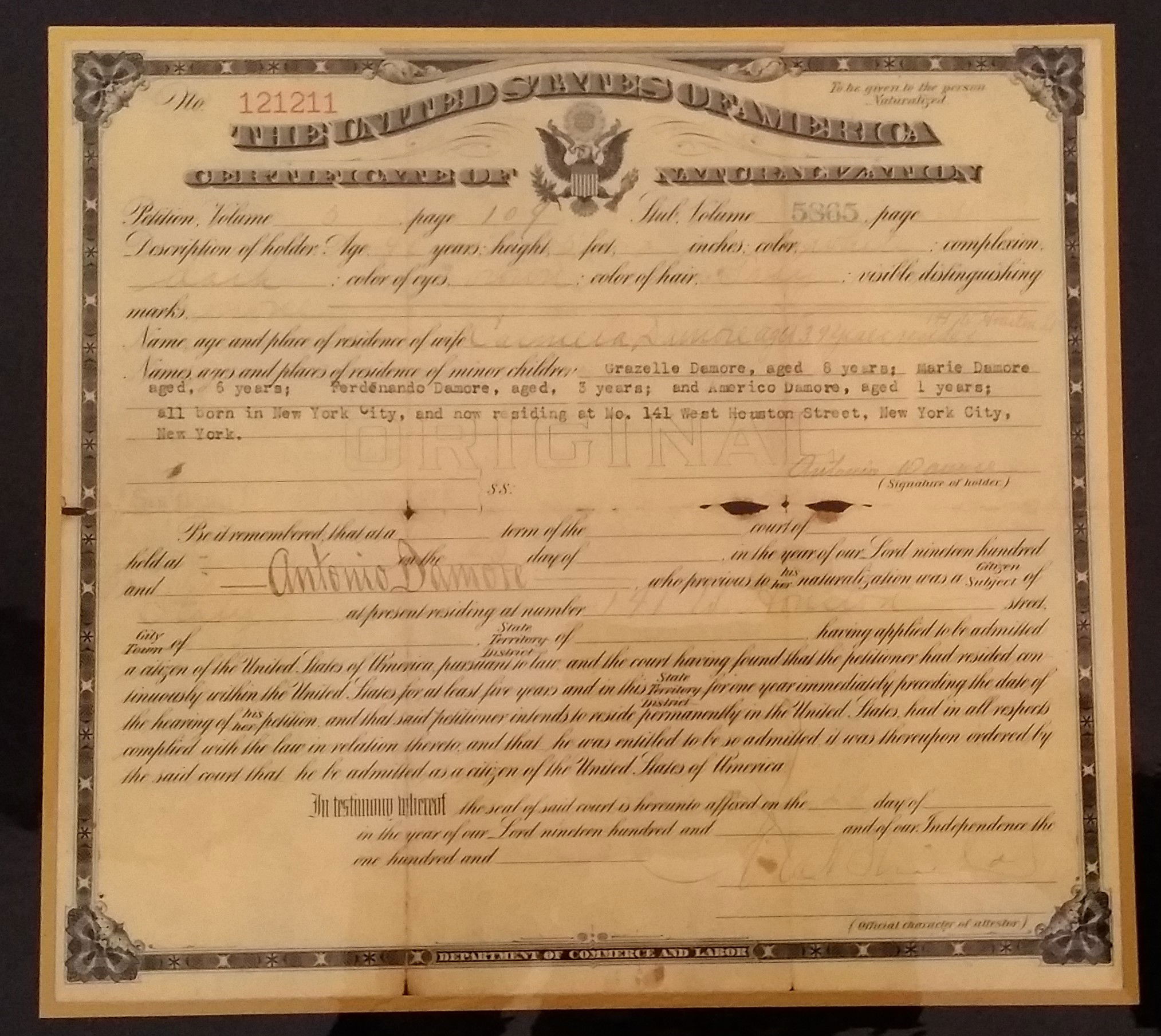

Antonio was naturalized as a US Citizen on Jan 20 1906, in New York, New York.

Antonio’s son Americo James was born on March 6, 1908, at 141-3 W Houston St New York, New York.

Americo would go on to play football for St John’s University on a full scholarship and would later work building military airplanes for World War II. He would marry his childhood sweetheart Lillian Breglia and have two children, Carmen and Anthony.

According to census records in the year 1910 Antonio lived at 141 West Houston St and worked as a Lamp Inspector for the “St Gas Company”.

Little Italy on Mulberry Street used to extend as far north as Houston Street, as far south as Worth Street, as far west as Lafayette Street, and as far east as Bowery. It is now only three blocks. Little Italy originated as Mulberry Bend. Jacob Riis described Mulberry Bend as "the foul core of New York's slums." The mass immigration from Italy during the 1880’s led to the large settlement of Italian immigrants in lower Manhattan, the results of such migration creating an influx of Italian immigrants which led to the commercial gathering of their dwelling and business.

Mulberry Street, New York City early 1900’s.

Bill Tonelli from New York magazine said, "Once, Little Italy was like an insular Neapolitan village re-created on these shores, with its own language, customs, and financial and cultural institutions." Little Italy was not the largest Italian neighborhood in New York City, as East Harlem (or Italian Harlem) had a larger Italian population. Tonelli said that Little Italy "was perhaps the city's poorest Italian neighborhood".

In 1910 Little Italy had almost 10,000 Italians; that was the peak of the community's Italian population. At the turn of the 20th century, over 90% of the residents of the Fourteenth Ward were of Italian birth or origins.

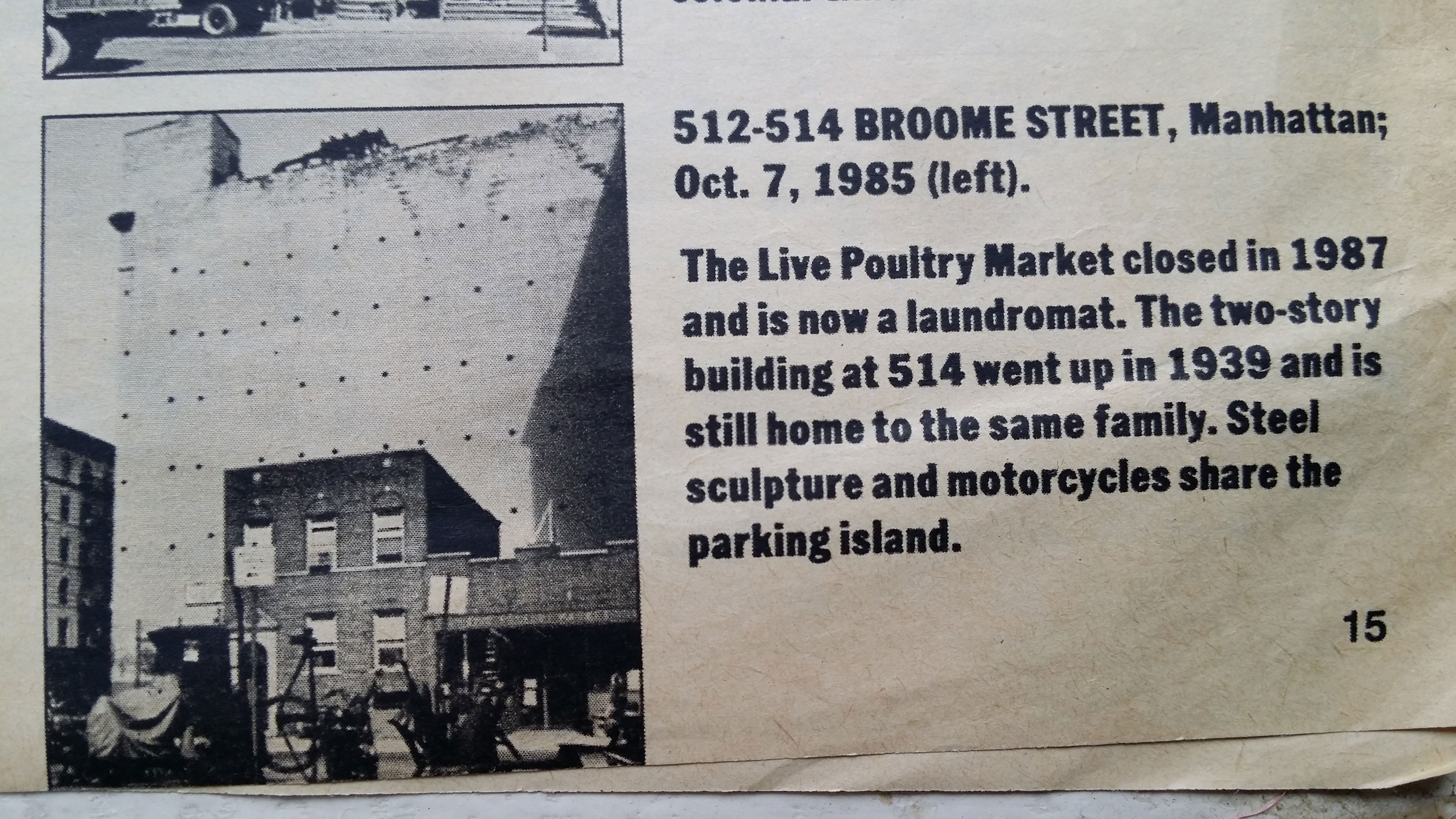

According to census records in the year 1914 Antonio lived at 438 W Broadway Oil and began working at the poultry market at 512 W Broome St as well. Live poultry or “wet” markets in the heart of the Lower East Side and other Jewish immigrant enclaves were quite numerous. Antonio was responsible for selling and preparing chickens for sale, which entailed performing “cervical dislocation” on live chickens in order to dispatch them humanely. This entailed snapping the chicken’s neck by hand. This was a very personal and hands-on approach to killing the chicken and could be quite challenging; a lot of people would carelessly break the animal’s neck which would result in a painful death as it is not done correctly.

One resident of the Lower East Side described her memory of the chicken market: “The smell was horrible. I remember picking a chicken. It quickly had its throat cut and flapped around a bit until it was put in a vat of hot water to remove the feathers.”

By 1919, an estimated 400,000 live chickens were sold weekly in New York City alone. The competitiveness of poultry industry gave way to a catalog of abuses. Some took the form of relatively minor infractions of the public trust in which retail butchers put their finger on the scale or, when charging by the pound, failed to account for the weight of the chicken’s feathers, while other violations were far more damaging. Price fixing; bomb explosions; physical assaults on rival poultry dealers, butchers and market men; putting emery in the engines of the competition’s trucks so they wouldn’t be able to operate; and employing known gangsters to do its dirty work were among the vices to which the industry fell prey.

By the beginning of 1917, with the United States only weeks away from entering World War I, grocery prices skyrocketed and the average cost of dinner exploded to $1.99 per meal—or $59 a month. To make a bad situation worse customers complained about getting much less for their money. To cut corners, for example, butchers who customarily trimmed away bone and excess fat before weighting meat abandoned the practice and began charging for these parts. Though the cost of living went up for everyone, it made dramatic differences in the lives of residents living in New York. Many were forced to pawn family heirlooms, alter their dietary habits, or cut back on meals altogether.

In 1915 Antonio lived at 438 W Broadway and worked as a “Restaurant Keeper”.

In 1917 Antonio lived at 512 Broome St and continued to work at the poultry market.

In 1920 Antonio lived at 384-386 Broome St and worked at the poultry market.

According to census records in the year 1924, Antonio and his family moved to 1251 73 Street in Brooklyn, New York.

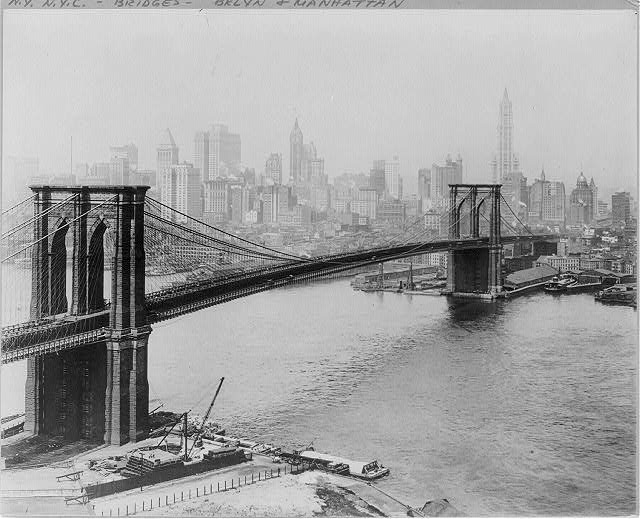

Brooklyn Bridge, 1900.

Italian immigrants dreamed of escaping the decrepit tenements and teeming streets of their neighborhoods, and throughout the 20th century their descendants did just that. Today large Italian districts are found in Brooklyn’s Bensonhurst and Bay Ridge (settings of the film Saturday Night Fever), Howard Beach and Ozone Park in Queens, Belmont in the Bronx, and Staten Island (where 55% of residents are of Italian heritage).

By the 1920’s Italian immigrants were flooding Bensonhurst; there were more than 100,000 persons of Italian ancestry in Brooklyn, which was comparable to the pre-1924 immigrations in Little Italy and East Harlem.

"When my grandparents came here, they were told not to speak Italian, that’s why none of us speak any Italian" - Christine Siano Carellini, a Bensonhurst Native, who came to Bensonhurst in 1916 from Italy.

Brooklyn, New York 1920.

While the next generation of Italian Americans from Bensonhurst did not have much in the way of European Italian customs, they did long to be connected to their heritage and ancestry in any way possible. Faced with considerable discrimination and poverty, Italian communities formed mutual aid societies, as well as clubs focused on culture (particularly music and opera), and organizations to stage religious festivals. Less benevolent organizations were the crime syndicates were based on Neapolitan and Sicilian secret societies which would later develop into the American Mafia. Although some Italian American customs differ from classic European Italian customs, the core values of both groups remained the same; a focus on family, food and faith.

Thanks to his profitable trade in 1930 Antonio owned their home, and it was valued at $12000, which would be about $191,892 in today's dollars.

In 1925 Antonio lived at 1255 74th St Brooklyn and worked in the poultry business.

In 1930 Antonio lived at 1251 73rd St Brooklyn and worked as a poultry market salesman.

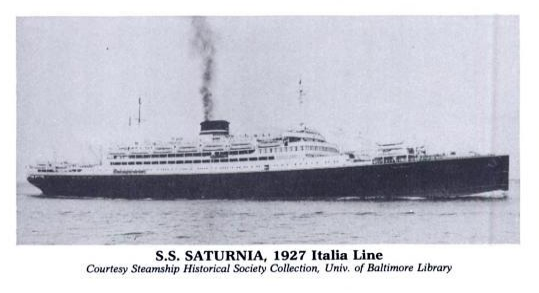

On September 5, 1930, Antonio and Carmela sailed from Naples to New York on the SS Saturnia after a return trip to Italy. The date of their embarking voyage is unknown.

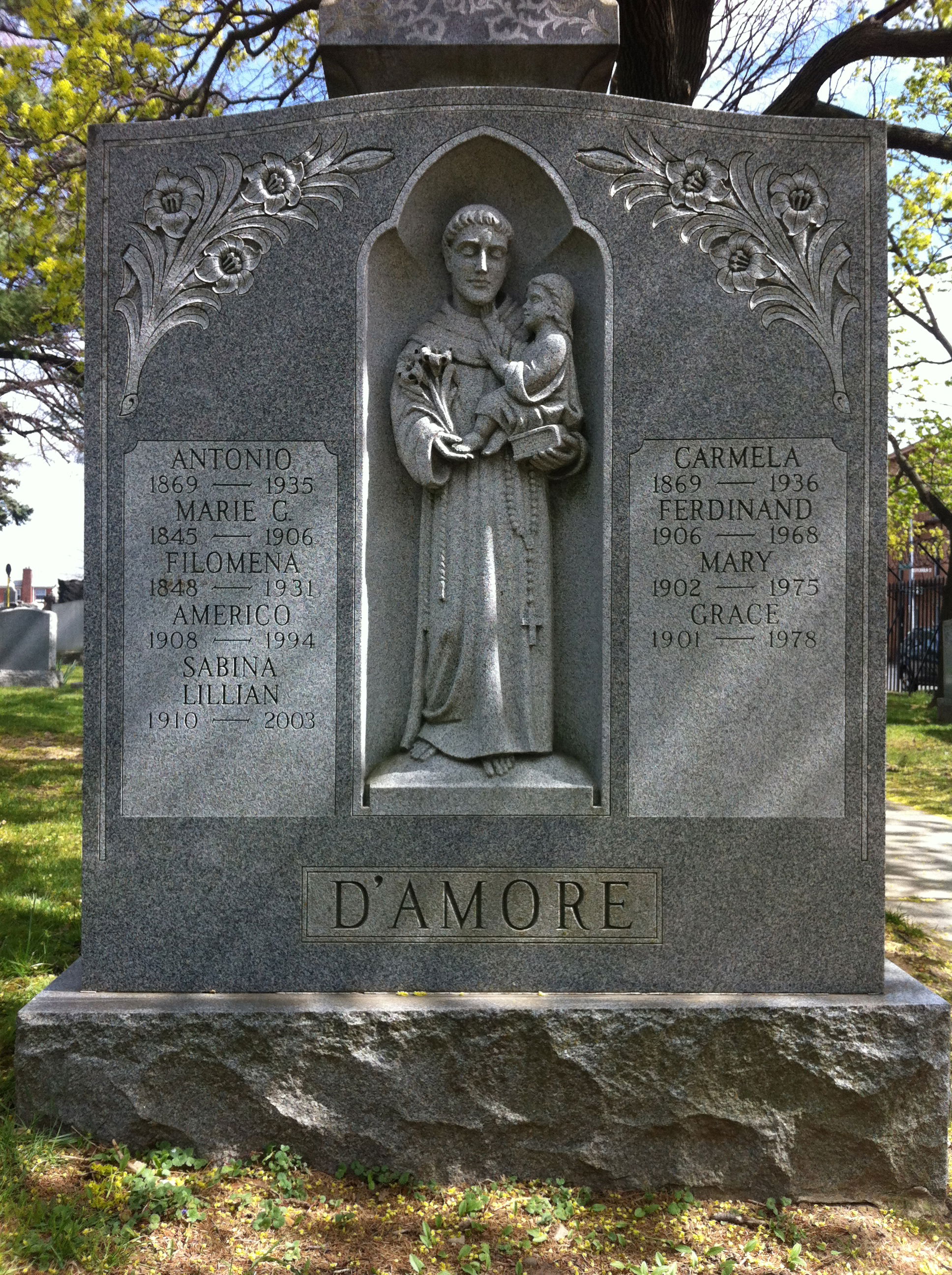

Antonio D’Amore died of heart failure on January 27, 1935, at the age of 65, five years before his grandson Anthony was born. He was buried at Linden Hill United Methodist Cemetery, in Ridgewood Queens, New York.

Thanks to his hard work, perseverance, and determination, Antonio was able to establish an American legacy, a feat for which his living ancestors have undying gratitude. They will continue to honor him and all the D'Amore family by preserving their rich history, by living according to their customs, and by passing them on to the next generation.